Improvisation and the death and birth of the framework 🌊 🌱

As I transition from my sabbatical back to work, I’ve been mapping concepts from art and jazz onto design.

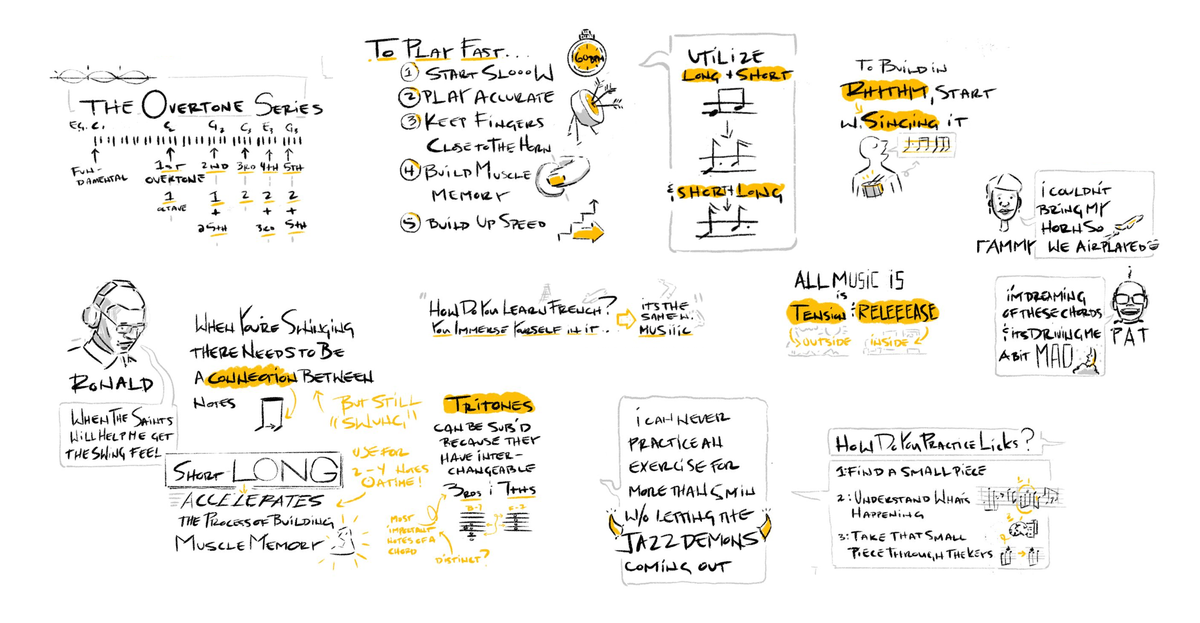

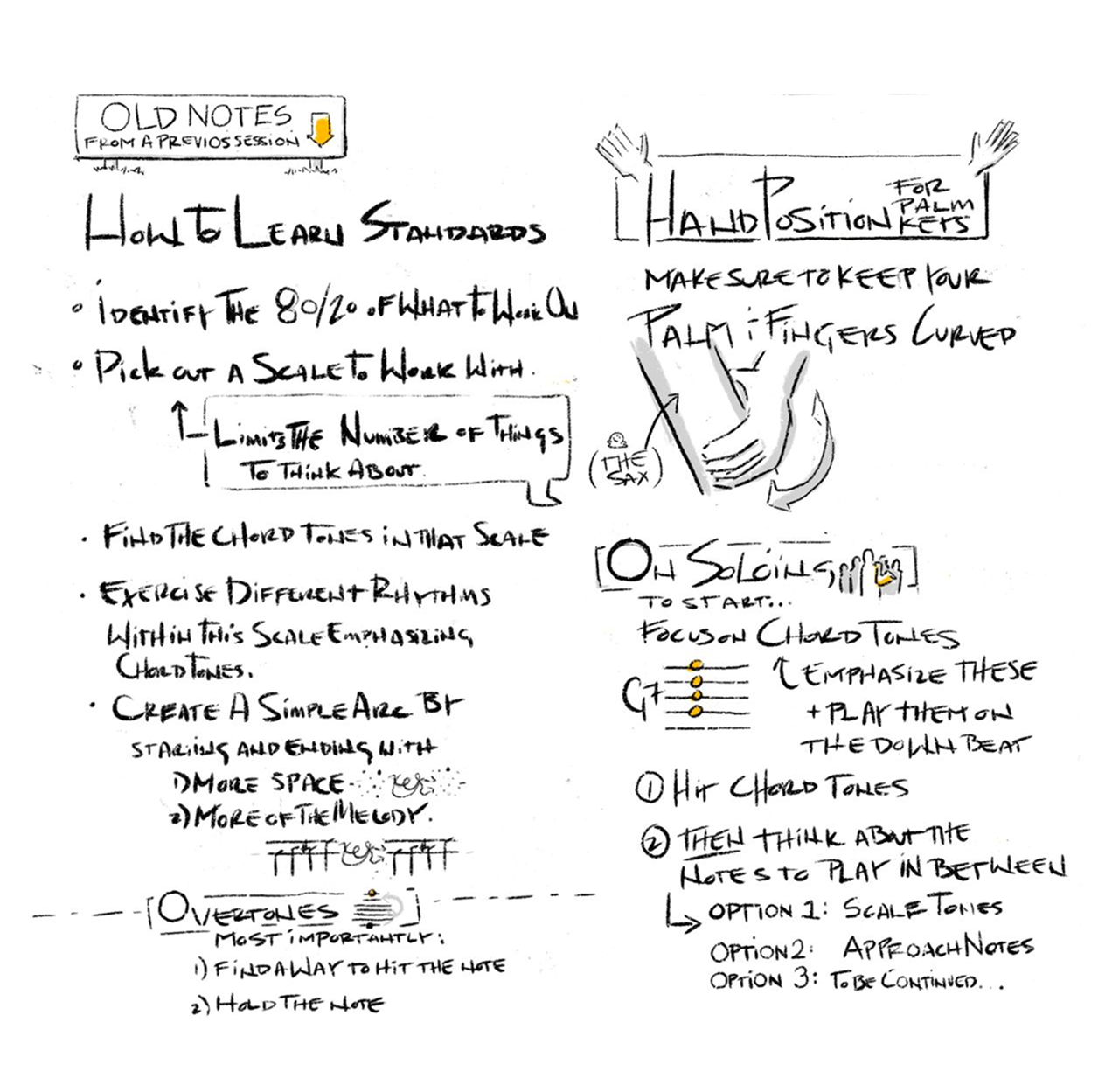

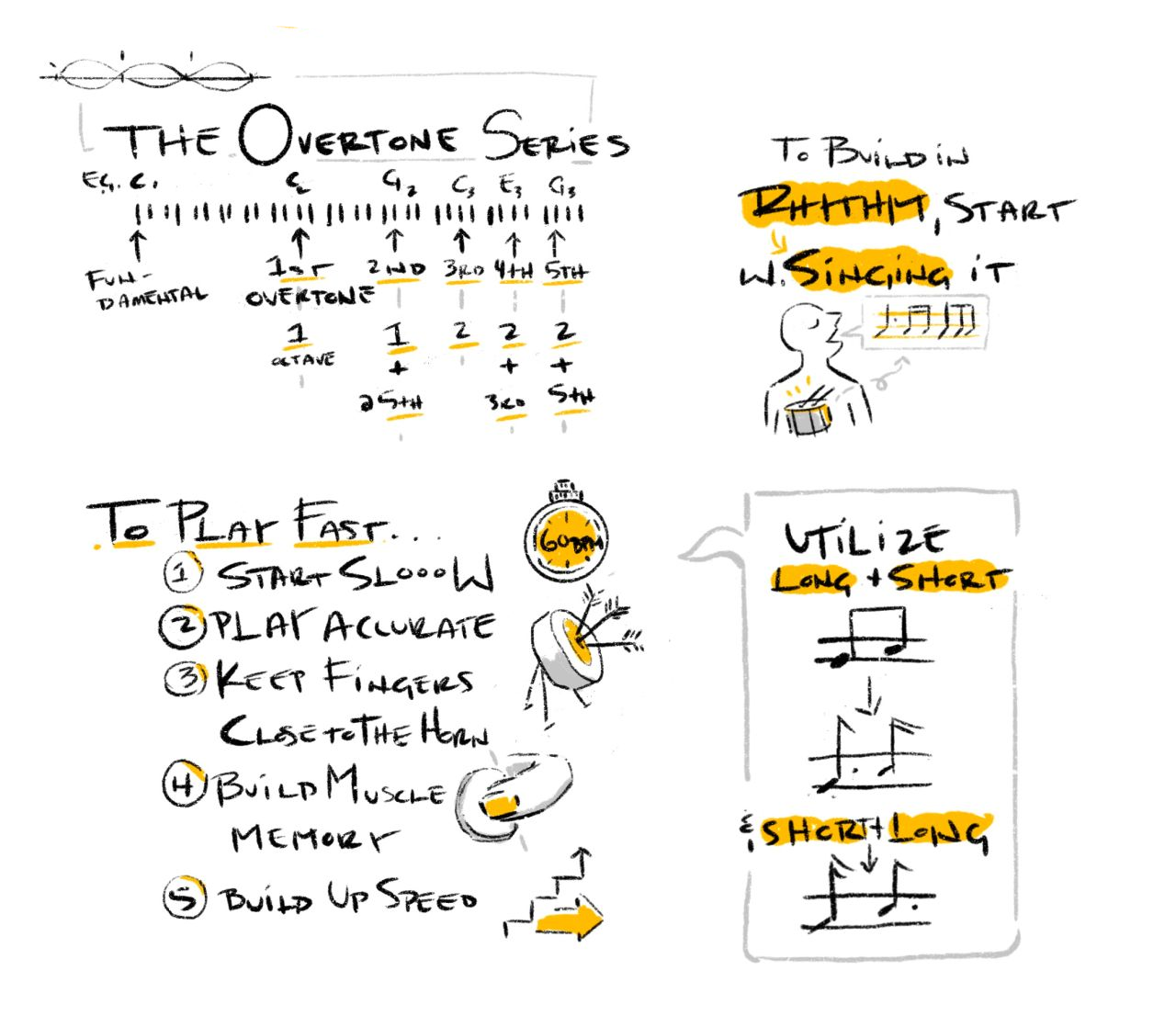

Here are some takeaways, along with sketch notes I made during a few saxophone master classes with the wonderful Alexander Mathias. Let's get to it.

The more you know the “changes” (the system/process), the more you can let go and play.

I spent my grad school years at the Institute of Design in Chicago—a fantastic program that, at the time, was on a mission to bring order to the messy world of design. I came out of that program with an analytical approach to making things, often reliant on frameworks to help me figure out where to go next.

Though useful, I’ve noticed that when I become overreliant on any diagnostic tool, such as a design framework, I risk missing opportunities to develop my own intuition. I now see frameworks, whether in music, art, or design, as a starting point for developing intuition rather than a static structure that can replace it.

Repetition builds familiarity. But it also can build boredom.

Repetition makes a new idea feel familiar—to us as creators and to our audiences. For creators, this familiarity frees up cognitive space to explore new ideas. For audiences, it gives them something to hold onto. But over time, that same familiarity frees up their cognitive space too, which can manifest as boredom.

The trick seems to be to take something small, like a lick, turn it into something familiar, and then add variations to it over time. This twist gives people something to hold onto while also surprising them. In design, Raymond Loewy described this as the MAYA Principle: creating the “Most Advanced Yet Acceptable” view of the future and making it real. Maybe when playing a solo, great musicians are doing the same thing. Do the musical performances that have had the greatest experiential impact on us not give us a tactile experience of the future that we previously never knew was possible?

Regardless, both musicians and designers seem to both be guiding their audience along the Csikszentmihalyi flow channel while bringing themselves along for the ride.

Frameworks can help with this.

But frameworks can also box you in.

In jazz, the framework is often the series of chord changes that underlie a a popular tune. These chord changes are referred to as just "the changes". Learning these changes is the starting point for understanding the harmony that supports the melody.

By learning these changes, a player can understand the palette of the most harmonious notes available to play at any given time. But it's often when a player plays notes that are not included in this palette, often referred to as playing outside, that a song can gain an additional emotional tone. In short, to riff off of a Charlie Parker quote: It's in learning the changes, and then forgetting or moving outside of them, that a player can use their instrument as an expressive medium.

Working it all out.

So how do we find balance between the structure that our brains both create and crave and the intuition and tastes we can build in our bodies?

For me, that learning has come through adopting creative practices, like jazz, which help me internalize the idea that frameworks aren't and can never be a substitution for intuition. They're just a home base. A point of departure. And, maybe more importantly, these practices remind us that no framework can replace the courage it takes to put our fresh ideas, and ourselves, out into the world.